Over an unusually sunny mid-October weekend, journalists and scientists from across Europe gathered again in 2025 for the fourth Climate Arena conference. This year we were in Budapest, where specialist environment and climate reporters came together for panels, workshops and networking sessions that delivered practical tools, project ideas and behind-the-scenes revelations.

Arena’s signature theme of collaboration was as strong as ever, with attendees making pitches to each other from panels, in networking sessions and at lunch tables.

At previous conferences, major investigations and journalism networks have been born – so we are excited to see the results of some of the new ideas we heard bubbling across two days of conversation.

We can’t possibly cover here all of the sessions, which focused on topics as diverse as false climate solutions, understanding deregulation, preparing for COP, and protecting whistleblowers in the Global South. However, we hosted a powerful forum full of important learnings that we know we can’t keep to ourselves. So, here is a collection of some of the things we learned at Climate Arena 2025.

The Journalists, activists, and civil society organisations unite? session explored the ways journalists are navigating a shifting landscape between our traditional ‘observer’ role and a more active, campaigning stance, often achieved through collaboration.

Historically, journalists – like scientists – have maintained strict boundaries between the work they do and the impact they believe it could or should have, avoiding political engagement. However, in this age of ‘polycrisis’, where journalists are coming together to expose, for example, major public health issues and governmental failures to remedy them (such as the Forever Lobbying Project, co-ordinated by panellist Stéphane Horel) the question increasingly asked is: is observation enough?

Claire Nouvian of Bloom, an NGO focused on ending the ravages of industrial fishing, outlined the difficulty of convincing mainstream media to work with them, despite their many campaigning wins. Horel and Nouvian noted that campaigners and journalists are often working on the same issues and, rather than seeing themselves in competition, can share findings and coordinate the timing of publications or actions to amplify impact.

Ultimately, the session called for a clearer framework to define different levels of collaboration (co-production, partnership, alliance) so that these new relationships can be more readily recognised across journalism, activism and civil society spaces. Many in the room offered to be a part of developing this framework; a perfect demonstration of the collaborative generation that Arena’s conferences are known for.

The session on Investigating multinational corporations destroying biodiversity in the Global South (while protecting your sources) explored how corporations get around international law, and how important it is to protect and support individuals who expose them.

Yann Phillipin of Mediapart outlined their work on the Greenfakes series, which exposed documents, leaked and contextualised by whistleblowers, that outlined the mechanisms by which major energy companies destroy biodiversity in the name of ‘development’, and the toothlessness of statutes aimed at environmental protection.

Greenfakes showed that, despite the World Bank’s requirement that any project financed by its International Finance Corporation (IFC) be ‘biodiversity neutral,’ consultancies hired to assess biodiversity impacts often delivered a ‘license to destroy’. The illumination of these mechanisms – such as giving CEOs final approval of a report, or reducing the contract’s ethical consideration segment to ‘professional confidentiality’ – provides us with rare insight into how environmental destruction continues despite laws and regulations put in place to prevent it.

But documents alone rarely capture the human realities behind corporate misconduct: what is said, implied, or ignored within organisations matters deeply.

Only whistleblowers, who often face serious risks ranging from being fired to being killed, can provide this. Gabriel Bourdon-Fattal of Climate Whistleblowers outlined that without his organisation’s protection, crucial for uncovering this inside information, many would not come forward. Climate Whistleblowers focuses on helping whistleblowers navigate the complex challenges specific to their situation – whether that means an understanding of their workplace dynamics, legal support, or physical protection.

Making your data move: Best practices for data videos outlined several ‘genres’ of data video: data commentary (personal, informal explanations of visualisations), data essays (narrative-led, a bit like scrollytelling), documentation (dataviz within longer documentaries), news segments (data used to contextualise broadcast stories), and data ‘physicalisation’ (playful representations of data, using the body or inanimate objects, for example). Understanding which format suits the message is crucial for effective storytelling.

Ciara Cesaro-Tadic, who makes TikTok videos for a number of German media companies, shared her approach of visualising data in a simple way to provide context rather than trying to outline a whole story via video. She emphasised that for social platforms, a strong opening hook is essential to maintain engagement, but so is planning the visualisations first to ensure your voiceover and signposting of the information is smooth.

Constanze Bayer, who works in German public broadcasting, used examples from The Pudding illustrating how thoughtful pacing improves comprehension. Complex graphics presented too quickly lose viewers, while clear, well-timed visuals hold attention. The speakers concluded that effective data videos blend storytelling, accuracy, and design discipline: visuals must be proportionally correct and easy to follow, as audiences remember what they see more than what they read.

The session on Doing stories in tough climates highlighted the shared challenges of doing investigative and environmental journalism under restrictive or hostile conditions across Central and Eastern Europe.

Speakers from Croatia, Hungary, Serbia and Turkey described how corruption, censorship, and threats – both legal and physical – create a climate of fear and hinder accountability reporting. Official data is often unreliable or manipulated, while freedom of information requests are routinely ignored or met with evasive responses. Yet, Dina Djordjevic, editor-in-chief at the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia, said even failed FOIA attempts can help identify potential whistleblowers or sympathetic insiders.

Despite limited data and financial support, the speakers stressed the importance of fieldwork, local networks, and perseverance in breaking through on otherwise repressive scenarios. Collaboration with peers facing similar constraints, rather than relying solely on Western European partners, helps preserve understanding of local realities, as well as securing funding that doesn’t compromise autonomy. In tough climates, integrity, creativity, and solidarity are essential tools: success can look like maintaining access, credibility, and trust amid systemic pressure.

And finally, Climate litigation in the age of misinformation explored how the process and results of legal action can be teachable for journalists in how to drive accountability in the climate crisis. In an age of misinformation where activism and public debate are easily dismissed, and journalists are under huge financial and time pressure, we can learn from the meticulous and often telling results that climate litigation can produce.

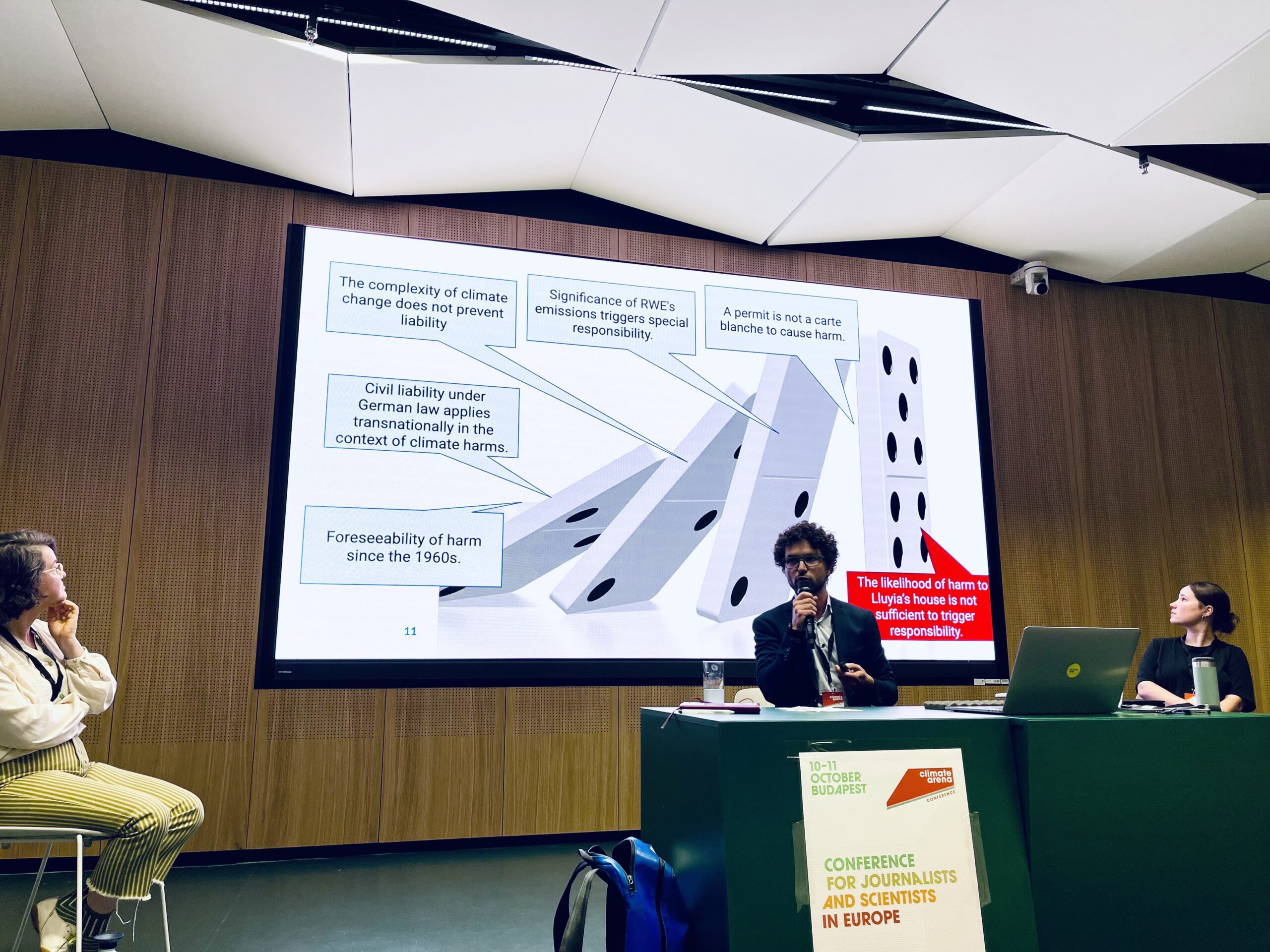

Sébastien Duyck from the Center for International Environmental Law reflected on the gap between public narratives and legal realities. He described how current cases depend on a ‘domino effect’ of legal arguments, where progress in one or more areas can unlock future victories, even if the case is ‘lost’.

Along with filmmaker Mette Reitzel, this was demonstrated with a specific case study. Reitzel’s upcoming film Where We Stand makes global legal battles relateable through human stories, such as that of Saul, a Peruvian farmer suing German energy giant RWE for contributing to the melting of Andean glaciers that threaten to flood his home. The case not only highlights a broader moral and legal question – how to define and prove risk in court, turning abstract responsibility into enforceable accountability – but also the crucial nuances most media missed when reporting on the verdict.

As RWE put out its press release before the judge had even finished speaking, most media picked up that the suit had ‘failed’. However, the process and verdict gave precedent for civil law to be used in future to hold companies accountable for the environmental effects of their emissions, in the event of a clearer direct link between the complainant’s home and the flood plain.

***

We’re incredibly proud about this year’s successful conference, and we will see you in Mechelen next May, for Dataharvest!